Design of scheduling and rate-adaptation algorithms for adaptive HTTP streaming

Hey there, I have done some science

In 2013 I was given the opportunity to publish an article as part of the SPIE conference proceedings in San Diego 2013.

The article can be found in the SPIE digital library. The original document can also be found here.

This would not have happened without the very valuable help of Yuri Reznik. I’d like to thank him (once again) a lot for this!

Thanks as well to my former thesis supervisors and later Fraunhofer HHI colleagues Yago Sanchez, Thomas Schierl, Cornelius Hellge and Prof. Thomas Wiegand. My own Masters Thesis in Engineering I did with their supervision in 2012 about the same subject was substantial to the contents of this article.

Now I have this blog (4 years later! :D). So I want to give a quick overview to the contents of this article.

Let’s start by an intro to the topic, then an overview of the solution approach. Furthermore, point to some examples of real-life implementations in some of the existing adaptive streaming libraries. Finally we’ll point to different solution approaches that have been produced by research lately in the field (BOLA algorithm).

Maybe I can explain some things I was doing research about in plain english :)

What is adaptive streaming?

Adaptive streaming over HTTP is a general concept to allow live or finite on-demand audio/video content streams to be transmitted through web infrastructure through channels with varying bandwidth/latency towards a wide range of device types (screen resolutions and decoding capabilities) - thus the term “adaptive”. The receiver clients’ streaming engine can potentially select and switch across various qualities/bitrates/resolutions or audio channel numbers and codecs, depending on the given conditions on the receiver side.

How to make that work?

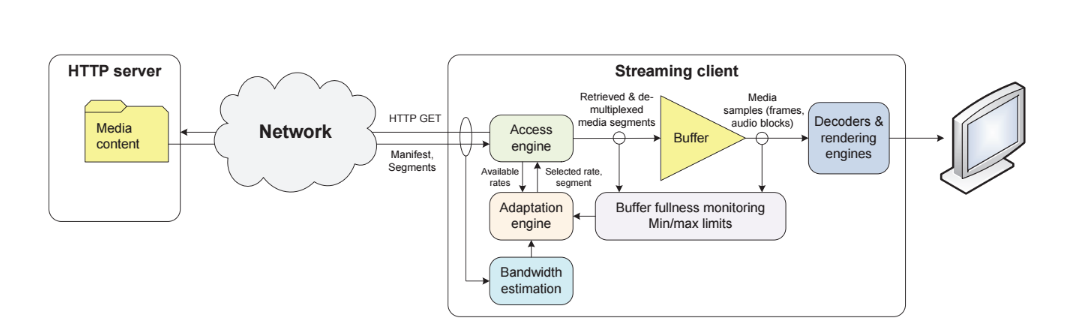

What defines an adaptive streaming receiver client, is the technique used to schedule HTTP requests that will contain segments of the stream it needs to display. In order to have a uninterrupted streaming session, the streaming engine needs to keep the playback buffers sufficiently filled at all times. That requires to select appropriate stream(s) bitrate(s) that will be transmittable through the channel we have at disposition.

When having a live stream, the potential buffer size one may have is limited, therefore “pre-buffering” all of the stream in awesome quality is not a solution. Sorry :) Also, one usually wants to watch a stream asap. Even more, the buffer size in memory is limited on many devices (especially web browsers) to very tangible amounts. This becomes even more a problem as our streams become heavier with HD and 4K resolutions.

Let’s consider that all streams can be seen therefore as live, and that the maximum buffer size one may have can only be up to a 120 seconds or less (in real live broadcast cases we usually talk of not more than 30 seconds). This assumption should help us to understand the trickyness of the problem :)

Channels on the internet are chaos

A client does not know per-se anything about the channel capabilites. Plus, due to the nature of the internet, channels are unpredictable in the first place. Therefore we have protocols like TCP which have clients/servers/routers create a self-regulated distributed system in which we try to balance out the overall traffic on the network. A client can only make an educated guess of the virtual channel properties it has at disposition - what it sees is really an aggregation and chaining of many physical channel models, modulated by the unpredictable behavior of other peers with which it is sharing the network.

That means in practice: When I perform an HTTP request, i.e a download of some resource, the transmission rate, the amount of bytes per seconds loaded, is chaotic and may vary along the transaction phase.

That is how TCP/IP i.e the internet works. We are allowing reliable transmission of messages between all peers, the price for that is an overall unreliable latency and bandwidth in performed transactions.

Therefore an adaptive streaming client needs to make an estimation to approximate the correct bitrate to select, eventually based on previously recorded statistics within the same streaming session, i.e using the same connection and thus exposed to similar transmission conditions.

What we want is to make a good estimation of the bandwidth we have at disposition from an HTTP clients’ perspective.

A classic signals and systems approach

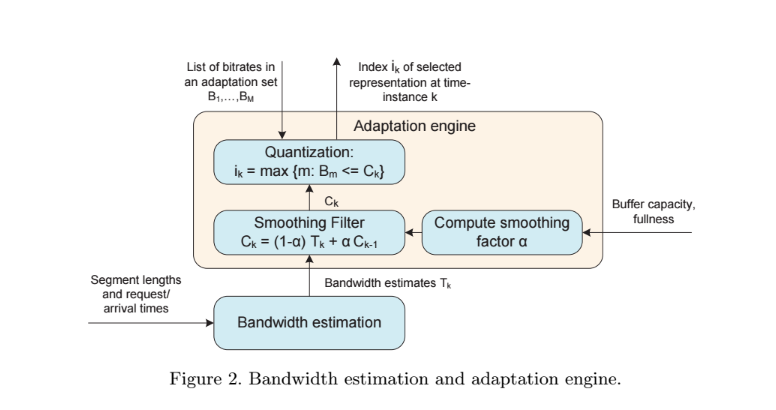

The approach of this article is to use a typical estimator approach of signals and systems theory: The exponential smoothing filter.

We are simply feeding the filter with bandwidth measurement samples - a bandwidth measurement sample is in fact a transmission rate measured along a transaction. That may be the average over the whole request or the differential sample on a recorded trace along the received response bytes. There is a whole lot assumptions and approximations about the properties of the stream and its segments, as well as the way the measurements are done to be made in order for this approach to be valid. I’ll spare you the math here :)

What comes out of the filter may be a really good guess for what bitrate to select next in your streaming session. In terms of statistics this kind of filter really is something that gives you an average of previously input values. The nice thing about it is that values are all weighted by their “age”, in an exponential manner. Physical systems often have exponential laws in them, therefore it may come in handy to predict a chaotic thing like the internet with something exponential, right?

Taking experiences into account

What really is helpful here is that one can take old “experiences” into account, but they will eventually fade away completely, and newer inputs will always have a much bigger weight. Which is important when you need to “adapt”. Compare this to an averaging weight that may be linear, or even flat, you may run into serious problems over time as new inputs may become insignifcant compared to the weight of thousands of previously recorded samples. This is why usually one talks of a “moving” average. It only takes into account so many previous samples and “forgets” about the older stuff. Moving averages also uses so-called windows usually to weight the piece of samples it looks at. That is also a valid approach, it just has different parameters to optimize on. An exponential smoothing filter can also be seen as a special case of a moving average, one which has an exponential window.

An exponential smoothing filter has one parameter, the so-called alpha. It basically tells you how much smoothing the output value should get. A lot of smoothing means that little spikes wont be visible, on the other hand the filter will be slow to react on step increments of the input signal - it is “slow”. Little smoothing will make the filter “fast”; on the other hand you may get “noise” on the output which you may not want in form of little spikes or statistical outliers.

The trade-offs

You get the idea: It’s a trade-off, there is nothing like the perfect alpha for all cases. It’s all about what you want to bet on. Fast averaging will give you a very reactive behavior towards changes, but you may react too quickly, take a spike for general improvement of conditions, switch up your quality and … BAM. Buffer under-run. Too aggressive. On the other hand, a slow filter may be “safe”, but it may lead to select a bitrate much lower that what the conditions would actually allow for.

What the article suggests is to use a smoothing parameter depending on the buffer size we are aiming at. When using a short buffer, or when the buffer has not built up much yet, we should have a slower smoothing alpha. When using a large buffer, we should apply more smoothing. Does that make sense? Again, this is one solution with it’s pros and cons. We said that a fast alpha is less safe, so why is it better with a short buffer, shouldn’t we be more “conservative” there. It depends. A fast filter will also be fast for switching down, which is something very important when your buffer is short. When you have a long buffer, you don’t need to react to quickly on a little down-ward spike. There is no way to react quickly to negative inputs, and at the same time have optimimum quality. What this optimizes for is quick reaction when we potentially are at risk of a buffer under-run, while optimizing for quality stability once we are not at risk anymore.

The problem with is that one may over-estimate quickly when in the “fast” mode, at times where buffer is short. We can avoid that by having the adaptation engine have a switch-up threshold in this specific state. In that way, we can take advantage of the fast “emergency” switch-down capabilities, while not going at risk to under-run from an over-aggressive switch-up.

This may have the quality generally be lower than it “could” in the buffer build-up phase that may occur at the beginning of a streaming session.

Similar approaches and existing implementations

The whole approach has also been discussed in other litterature, there are a whole lot of articles with similar approaches. Also implementations around that use these similar approaches. One of them is the Shaka Player project.

Shaka implements an exponentially weighted moving average. It is a something a little different from the simple smoothing filter we use: https://github.com/google/shaka-player/blob/af252c94e73344a4a279760a85e8c14187d87268/lib/abr/ewma.js

Then the bandwidth estimator it uses simply takes the output of two of these filters, one slow, one fast and uses the “worst” estimation: https://github.com/google/shaka-player/blob/af252c94e73344a4a279760a85e8c14187d87268/lib/abr/ewma_bandwidth_estimator.js

Very similarly, another adaptive streaming library, Videojs-contrib-HLS, uses the same approach as well: https://github.com/videojs/videojs-contrib-hls/blob/8a229d3364db63c9e6f87f6c546f7f1e428e2560/src/playlist-selectors.js#L262

Different approaches based on buffer state

In our approach, we are talking a lot about sampling the transmission rate, and parameterizing the estimator with the buffer state.

The probably much more precise and developped approach of the so-called BOLA algorithm samples the buffer state.

It is a different approach that has proven to work very well: